Languages may vary from Buenos Aires to Bangkok, Montreal to Moscow, but almost every street seller and cab driver in the world is familiar with a single term that gained notoriety during a boisterous U.S. presidential campaign almost 200 years ago.

“OK” is a small word that has a powerful impact. This indicates “yes” as well as “I understand.” It is a noun: My editor gave me the go-ahead for this story; a verb: She gave her approval; and an adjective:It was a good narrative.

It’s even a straightforward interjection: Alright! The grammar lesson is over!

“No matter my bad language skills, ‘OK’ is sort of universally understood,” says Lauren Frayer, a London-based correspondent for National Public Radio who has covered stories from dozens of nations in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

The invention of OK is distinctly American. Although it began as a jest, it has since grown to be one of the most commonly used words worldwide.

The Word of the Week article this week explores its development.

Where did OK come from?

For a large portion of its existence, the meaning of “OK” was unclear, and some people continue to question the most widely accepted theory. There have been many ideas over the years, with some linking it to Scottish or French ancestry. Pete Seeger, a folk musician, popularized the notion that “Choctaw gave us the word OK” in the 1960s. This was a generally accepted assumption at the time, however it turned out to be untrue.

According to a 2011 article in the Dictionary Society of North America’s Dictionaries Journal, “early efforts to establish the origin of OK were imaginative at best, without documentation, and often just foolish.”

The majority of academics today agree with the findings of Allen Walker Read, an English professor at Columbia University who began working to solve the origin of OK in the 1960s. Following its path, he discovered that “all correct” was jokingly misspelled as “oll korrect.” Although “it had probably been used colloquially before that,” according to Doug Harper, creator of the Online Etymology Dictionary, the term was first mentioned on March 23, 1839, in the Boston Morning Post. Its roots are in a humorous linguistic craze of the era, similar to Cockney rhyming slang, when people “would abbreviate common phrases with deliberate, jocular misspellings,” he claims.

The editor of The Baltimore Sun used the word in a piece in July 1839.He’s grateful to “some anonymous gentleman for a gift of bottles of wine and he pronounces the wine ‘O.K.,'” recalls Harper.

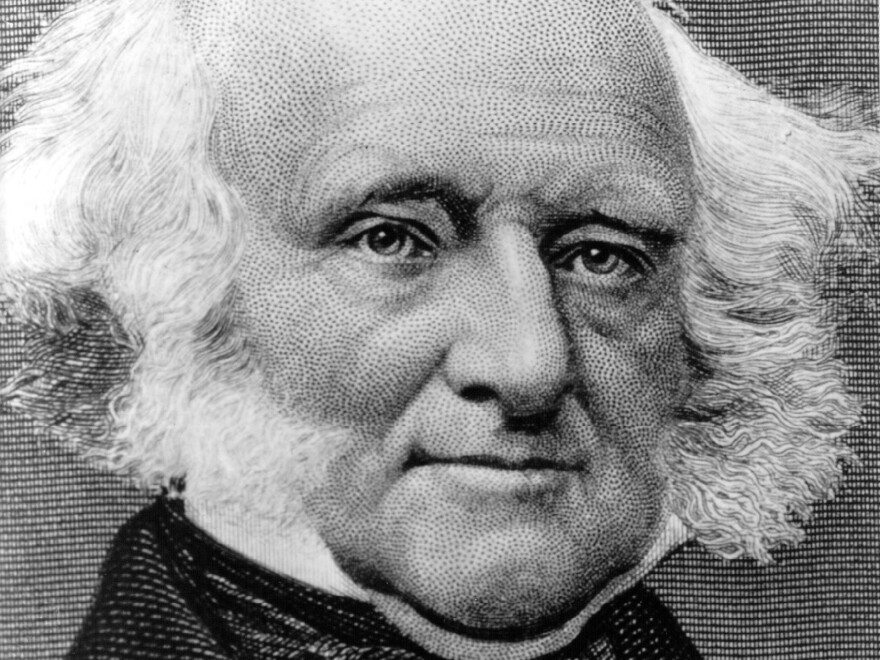

However, the word really came into its own in 1840, the year after, during President Martin Van Buren’s reelection campaign.According to Mark Cheathem, a history professor at Cumberland University and project director of the Martin Van Buren documents, “conveniently O.K. lined up with a nickname that was attached to Van Buren ‘Old Kinderhook,'” referring to the president’s birthplace in Kinderhook, New York. According to Cheathem, political nicknames were popular during the time. Andrew Jackson, Van Buren’s predecessor, was referred to as “Old Hickory,” and William Henry Harrison, his opponent in 1840, was called “Old Tippecanoe.”

“O.K. Clubs” were established by Van Buren’s followers to energize the candidate’s base of support, according to Cheathem. The clubs reportedly added “muscle” to the campaign as well, according to some earlier reports. In an effort to strengthen the association, Van Buren even started signing documents with “O.K.”

Harper points out that both sides used OK in the 1840 election, with some publications at the time asserting that Jackson’s misspelling of the word was intended to make fun of the former president, a fellow Democrat like Van Buren. According to the tale, Amos Kendall, Jackson’s postmaster general, was charged with improperly managing finances. After personally confirming them, Jackson gave the order to bundle them and label them as “OK” as, in his words, “Amos is all correct.”

How has OK changed over the years?

OK, of course, caught on. It was helpful in a technical age that started with Morse code and telegraphs since it was simple to pronounce and could be employed in a number of contexts to indicate basic agreement, confirmation, understanding, or acceptance.

“It’s a perfect headline word because it’s so short,” Harper asserts. “In print it’s difficult to figure out how [to] spell it out,” he claims. On the contrary, “it was also an abbreviation you could write with just two letters … and it covers a lot of ground, meaning-wise.”

Harper claims that American soldiers serving overseas contributed to its increased use in the 20th century. “If you’re looking for the global spread, I would really start with the two world wars and right after them,” he states.

In 1945, Harper claims to have observed instances of “people either celebrating or complaining that the French are starting to use OK, which would be the ultimate [barrier], I suppose, for such American slang.”

The word “A-OK” was made popular by NASA astronauts in the 1960s to indicate that all systems were operational. Additionally, “OK” was one of the first words sent from Earth to the Moon 56 years ago this week. “OK, Neil, we can see you coming down the ladder now,” Houston said as the television signal turned on and Neil Armstrong got ready for his well-known “one small step.”

Nevertheless, things haven’t always gone well for OK. Originally, the word was an initialism, or more specifically, an abbreviation, in which the first letters are pronounced independently (unlike an acronym, which pronounces the first letters as a word). However, this has caused misunderstanding on how to render it. Is everything alright?

Although Harper claims that he favors “okay” because “it doesn’t break up the page with a lot of capitals,” NPR generally follows the Associated Press style, which suggests using “OK” without any periods.

Why does OK matter today?

OK is “very probably the most widely recognized word in the world,” according to Merriam-Webster.com, according to the dictionary.

Although it is typically a spoken word rather than a written one, it appears on lists of the most popular SMS words, along with its even shorter and more contentious counterpart, just “K.”Naturally, there was the contemptuous “OK, Boomer” a few years back.

Harper claims that it would be nearly impossible to eradicate the word now. One advantage is its imprecision. “In street talk and casual interactions, vagueness has more value than precision,” he states. “We keep reinventing those [kinds] of words.”

Copyright 2025 NPR