Reading immigrant books that challenge the concept of home is very enjoyable, particularly when it is examined as a pain or memory that one revisits and reworks to fit one’s preferences. These stories are frequently about migration, displacement, and the quest for belonging, especially when they are intricately and thoughtfully crafted.

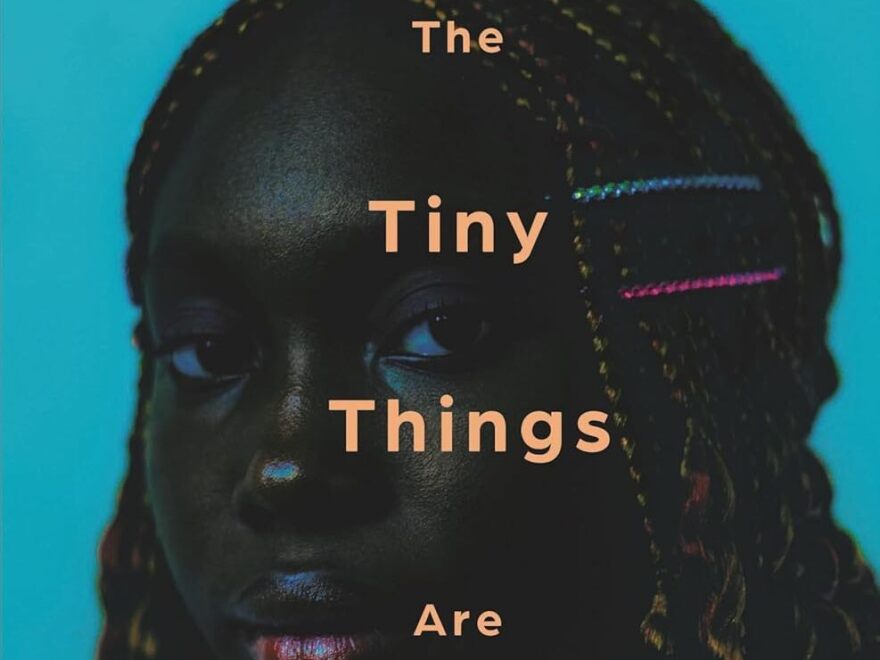

Esther Ifesinachi Okonkwo joins the ranks of authors who have done it well with her debut book, The Tiny Things Are Heavier.

The protagonist of this tale is Sommy, a PhD student from Nigeria who recently moved to Iowa and is plagued by guilt about abandoning her brother Mezie after he attempted suicide. She is experiencing homesickness, confusion, and a growing sense of dislocation as she moves between two different places. She starts a romantic relationship with Bryan, a mixed American guy who is separated from his Nigerian father, and forms a perplexing bond with her Nigerian roommate, Bayo. As Sommy clings to the comforts of home, particularly when her brother rejects her frequent attempts to contact him, her connection with Bayo takes shape. While Sommy appears to be thrashing aimlessly, Bayo eagerly devours everything America has to offer, and she sees a lot of her brother’s ambition in him. The ties between Sommy, Bayo, and Bryan serve as a framework for the novel’s examination of race, loss, and the frailty of intimacy and family. Cultural friction, estrangement, and desire are frequently at the heart of their encounters.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s rhythmic storytelling style is echoed in Okonkwo’s precise and purposeful words. In the early chapters, the tone, narrative restraint, and thoughtful interiority are distinctly Adichie-esque, making the resemblance nearly impossible to overlook. However, as the narrative progresses, Okonkwo’s voice starts to emerge in her own unique style, which she describes as being highly restrained, perceptive, and emotionally accurate.

The novel’s depiction of Black immigrants’ experiences with race in America is one of its strongest points. Sommy’s presence in the nation is characterized by disruption rather than excitement: An occurrence in which a white lady and her child are immediately labeled as “other.” This scene establishes a boundary between her idealized perceptions of America and the more startling facts of the nation. Even the most casual interactions, such as when a white student tried to “translate” Sommy’s argument in one of their classes, further upend Sommy’s understanding of race, class, and selfhood. Sommy yells at the brunette, “I’m glad someone here speaks African,” and wishes she had done the same to the white mother who reprimanded her. Like many Americans, Sommy is disillusioned by that point and views nearly every encounter she has with a person of a different race as a potential battlefield. She is pulled farther away from the conviction she previously had about herself and the world by these moments, which mount up like time weights.

In the end, her connection with Bryan becomes the main focus of the story. Despite being biracial, Bryan has an American perspective and stance, ingrained in a privileged Black identity that Sommy frequently thinks is out of reach. His knowledge of Nigeria is filtered via avoidance and distance since he is unable to communicate in her language, both literally and figuratively. He sees her relationship—or lack thereof—with her family in black and white and is unable to comprehend them. Being accepted as a Black guy in America is another problem for Bryan. They have complex, occasionally sensitive, but never entirely balanced dynamics. Sommy is torn between resenting what she might have to give up in order to belong, even to Bryan, and wanting to fit in.

Eventually, Sommy persuades Bryan to travel to Nigeria in order to look for his father and discover a sense of identity of his own. Sommy starts to realize how much America has subtly influenced her thinking during this trip, which is the second part of the book and where the differences between Black American and Nigerian culture are exposed: “Had Mezie become one of the Africans who referred to Africa as though it were a country? Or had she turned into one of those individuals who perceives power disparities in every situation?

In their efforts to change, Okonkwo’s characters are fearless and occasionally almost theatrical. For example, Sommy tries to blend in at school, while Bryan tries to give up his affluent upbringing in order to appear more “Black.” In this sense, Bayo is very intriguing. He is outgoing, theatrical, and appears comfortable in white environments, but he is also quite insecure and is always looking for approval. Through him, Okonkwo examines the more subtly humiliating aspects of assimilation, such the minor ways one has to change to blend in with a society that rarely accepts individuality.

The Tiny Things Are Heavier presents a close-knit, poignant portrait of a young lady torn between two worlds she longs to join, even though it doesn’t take the genre in radically different ways. The title’s “tiny things” are more than just metaphors; they represent the unsaid conflicts, cultural miscommunications, emotional strains, and covert betrayals that arise in every immigrant narrative. Okonkwo writes with poise and assurance, delaying her discoveries. By the book’s end, we are also reminded that the identities we attempt to create or give up in the name of survival can weigh us down more than the trauma we left behind.

Copyright 2025 NPR