One of the stated objectives of the first regulated wolf hunts in 2009 in Montana and Idaho was to ease the burden on ranchers. Livestock were being killed by wolf populations that were on the rise. It was believed that fewer wolves would result in fewer sheep and cows being murdered.

The European Union has agreed to decrease wolves’ protected status, and the same reasoning is currently being utilized in wolf management plans and being addressed in Europe.

However, according to a recent research, the loss of livestock in the Western United States has not been significantly impacted by wolf killing. Additionally, it hasn’t decreased the frequency of calls to slaughter troublesome wolves from federal or state wildlife officials.

One of the study’s co-authors, Leandra Merz, an assistant professor at San Diego State University, stated, “We’ve often just fallen under this assumption that if wolves are the problem and we kill some of them, the problem isn’t as bad.” “It does reduce predation a little bit, but not really what we hoped for.”

Data from two states that permit public wolf hunts, Montana and Idaho, as well as two that do not, Oregon and Washington, were examined in the study, which was published in the journal Science Advances. Researchers examined livestock depredation, wolf hunting and government removals, and wolf abundance in those states between 2005 and 2001. They discovered that killing one wolf saved around 7% of a single cow’s worth of livestock.

To put it another way, it would take about 14 wolves to preserve one cow. There are an estimated 1,100 wolves in Montana. It is estimated that there are more than 1,200 wolves in Idaho.

“Based on how many wolves you’d have to kill while trying to match conservation (goals), but also allowing ranchers to continue with their livelihoods, it might not be the best solution,” Merz said, referring to the goal of preserving cattle.

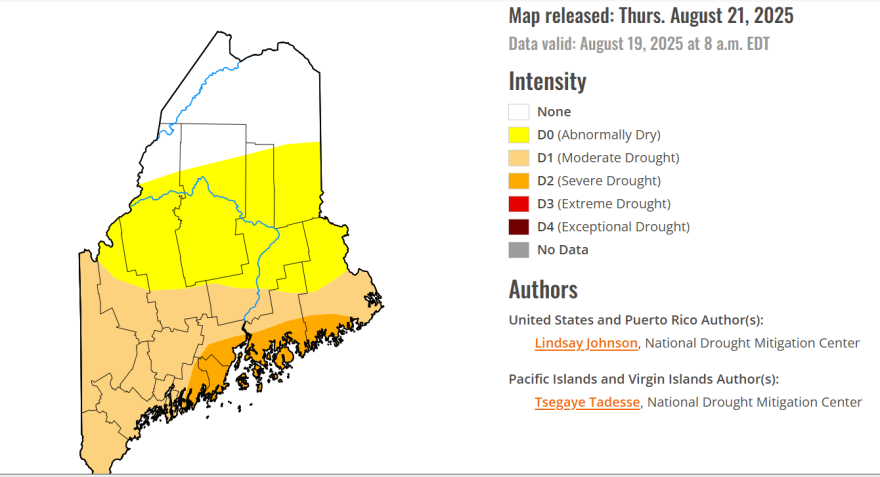

Many Western states have long employed non-lethal tactics, including as fencing or flagging grazing fields or hiring individuals to police their boundaries. However, Merz noted that the ranchers, who are already juggling numerous other demands including drought and wildfires, frequently bear the expense of those practices.

Merz, who has experience with human-animal conflict and wildlife conservation in Africa, stated that she and her team do not want the results to be used as a political talking point in the contentious discussion around the morality and benefits of wolf hunting.

“This paper isn’t about whether or not we should be hunting,” she stated. “We’re talking about finding a management tool that will help ranchers manage livestock predation.”

Managing human-wildlife conflict

Human-wildlife conflict is practically unavoidable when wolves repopulate an area, either naturally or with human assistance, as was the case in Yellowstone National Park and, more recently, in Colorado. Consequently, human-human conflict also exists.

Numerous lawsuits have been filed about wolf management and whether or not they should have federal protections. Wildlife organizations contend that gray wolves have not fully recovered as a species, whereas Mountain West states contend that populations have increased too much. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was ordered by a federal judge earlier this year to reevaluate hunting and other risks to gray wolf numbers in the Western U.S. after the agency rejected a petition by wildlife organizations to re-list the species under the Endangered Species Act.

In the meantime, wolf-hunting tactics and quotas have become more aggressive in Montana and Idaho. On Thursday, the Fish and Wildlife Commission of Montana will consider a proposal to raise the number of wolves that can be harvested in the state from 334 to 500.

An inquiry concerning the new report was not answered by Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks.

“But we can say that we manage all predators with a variety of goals, which include providing hunting opportunity, keeping predators in balance with other big game (prey) species, and reducing or minimizing social conflicts, which include livestock depredations,” said an Idaho Fish and Game spokesman, who declined to comment on the study directly because the agency had not had time to review it in detail.

297 wolves were killed by hunters and trappers in Montana in 2024. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Wildlife Services, Montana ranchers lost 62 animals to wolf predation during that time. Idaho Wildlife Services conducted an investigation into 99 wolf depredations between July 1, 2023, and June 30, 2024.

Federal wildlife agents are frequently summoned to remove wolves and other predators that harm livestock or pose a threat to people. Usually by killing it, or occasionally the pack.

The current study’s researchers examined whether public wolf hunting had decreased the necessity for those targeted removals because the process is costly and contentious.

Neil Carter, a senior author of the new study and an associate professor at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability, stated that if this is the case, one could argue that wolf hunts in Montana and Idaho have contributed to lower government spending.

However, that was not supported by the data.

The statement, “It didn’t matter which model we used, there was no relationship to the number of government removals of wolves in a county [to hunting] in the same year or the following year,” makes sense considering that public wolf hunting doesn’t target a particular problem area or pack of wolves that are hungry for cattle.

Carter did, however, express surprise at the lack of correlation between public hunting and livestock depredations. However, he stated that he thinks the study is relevant given the discussions taking place in Europe and the possibility of wolf hunting in states like Oregon, Washington, and Michigan if the species is federally delisted.

“If we’re going to tell the public that we think it’s going to help reduce livestock depredations, but it doesn’t, then we’re in a bind again because it doesn’t actually solve the problem,” he stated. “And you still have this strong divisiveness around this management tool.”

Copyright 2025 NPR